|

|

Show minor keys as:

Natural

Harmonic

Melodic

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hover over the "Circle of Fifths" to see the scale, chords, and fingering (click to lock / unlock). | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Learn more |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Scales are the key to understanding music. When a song is written in a certain "key" (i.e. "scale") it will only occasionally contain notes outside of that key. (Hence the scale is the "key" to the song!)

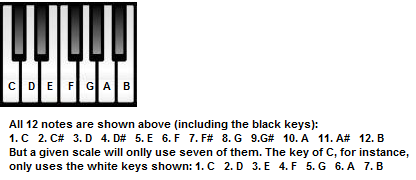

There are 12 different notes, but only 7 are used in each scale. (There are other types of scales such as the Pentatonic which uses 5 notes per scale, but we're not going to discuss these.) Each scale begins with one of the 12 notes, and ascends through a series of notes until it arrives at the starting note one octave (8 scale-notes) higher.

The scales are divided into two main categories: Major and minor. There are 3 types of minor scales, which we'll delve into in a moment. Our immediate comments will be for the Natural minor scale.

| Scales | |

|---|---|

| Major | minor |

| Natural | |

| Harmonic | |

| Melodic | |

A minor scale differs from a major scale in the pattern it uses to establish which note comes next in the sequence. In order to understand this, we first need to talk about intervals.

An interval refers to the distance between two notes. We can refer to the smallest interval as a half-step (or semi-tone): this is the interval from one note to the very next note. On the piano keyboard this would represent two keys right next to each other (whether black or white). For instance, from B to C is a half-step, and from C to C# is another half-step. A whole-step (or tone) is two half-steps. For instance, from B to C# is a whole step.

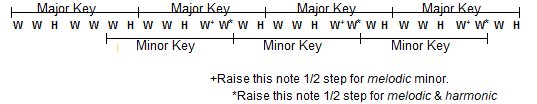

A major scale starts with one of the 12 notes and then proceeds upward following this pattern:

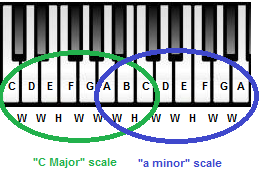

If you look at the piano keyboard you see that the white and black notes are not evenly spaced: some white keys have no black note between them. If you look at the keyboard starting with C, it is very easy to see the C Major scale: it follows the Major pattern given above by only using the white keys:

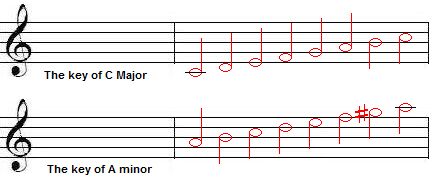

Notice the half-steps between E and F, and again between B and C where no black note lies between. There are no sharps or flats in the key of C Major. A key's signature shows the sharps or flats it uses. The signature is shown right after the Treble and Bass clef signs. The signature of C Major is blank.

As another example, let's start with the note G, and look at the G major scale:

By following the same pattern of whole and half steps, we find that the notes in the G Major scale are: G, A, B, C, D, E, F#. (Moving a whole step from E brings us to F#, since F is only a half-step from E.)

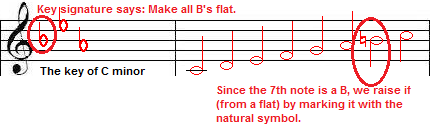

A minor key is related to a major key when it shares the same key signature. In the Circle of Fifths this relationship is shown between the outer and inner circle.

The minor key related to C Major is A minor. So, A minor has a blank key signature (i.e. no sharps or flats). It has the same 7 notes as the key of C, but it starts with the A note instead of the C note. Because of this -- because it starts on the 6th note of the Major pattern (3 half-steps from the top note: hence the name "minor third"), it skews that pattern as follows:

Or, you could look at a minor scale this way: it's the same as a Major scale pattern but preceded by a Whole, Half:

So, A minor (Natural) would contain the following notes:

A, B, C, D, E, F, G, A

For the Harmonic minor scale, the only difference is that we raise the 7th note a half-step. So, the A minor Harmonic scale is:

A, B, C, D, E, F, G#, A

Notice the g# (which is the G note raised a half-step.) Because the minor key shares the same signature as the major key, we need to include the sharp symbol before each occurrence of the note in the song (rather than once up-front in the key-signature.)

When the note occurs more than once in the same measure (i.e. before a vertical "bar" line) we only show the sharp on the first note of the bar (the sight-reader knows that it is meant to apply to all occurrences of the note in that measure.)

When a 7th note would be sharp according to the key-signature, we must "double-sharp" it in the Harmonic minor scale with a special double-sharp symbol. Compare B Major with its related minor key: g# minor.

Notice that the F is sharp in the key signature. Since this is the 7th note of the minor key we place the double-sharp in front of it on the Harmonic minor scale. (F double-sharp is the note G: F raised two half-steps.)

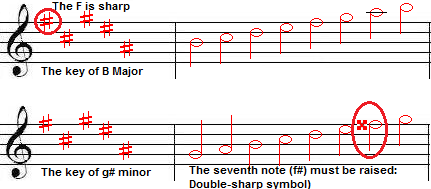

Conversely, when the seventh note of the minor scale is Flat in the key signature, we raise it a half-step by unflattening it: which we call making it "natural" [Unsharpening a note is also "making it natural"]. You can see the Natural symbol at work in the c minor scale (where the signature calls for B to be flat.)

The melodic minor is exactly the same as the harmonic minor except that instead of just raising the 7th note of the natural minor scale, we also raise the 6th note. So, the A minor Melodic scale is:

A, B, C, D, E, F#, G#, A

Notice that we not only raised the 7th note (from G to G#) as in the harmonic minor; we also raised the 6th note (from F to F#).

We've already seen two ways to find the minor: (1) start with the root note, and follow the step pattern: W-H-W-W-H-W-W. (2) Find the relative major for the minor key, use its signature, but start the scale on the minor's root note (e.g. for the key of A minor, find the relative Major key: C [always to be found three counter-clockwise steps on the circle of fifths]).

A third way is to take the same-named Major key (e.g. A Major for A minor) and flatten (i.e. lower by 1/2 step) the following notes in the Major key to arrive at the minor key:

| Note # | Template (Major to minor) | Example (A Major to A minor) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minor Type | Major | Minor Type | ||||||

| Natural | Harmonic | Melodic | Natural | Harmonic | Melodic | |||

| 1 | A | A | A | A | ||||

| 2 | B | B | B | B | ||||

| 3 | Flatten | Flatten | Flatten | C# | C | C | C | |

| 4 | D | D | D | D | ||||

| 5 | E | E | E | E | ||||

| 6 | Flatten | F# | F | F# | F# | |||

| 7 | Flatten | Flatten | G# | G | G | G# | ||

| 8 | A | A | A | A | ||||

Method 1 is useful when you're not familiar with the Major keys.

Method 2 is useful when you're reading sheet-music and can identify a Major key from its key signature (and then can look for indications in the piece that it's using the key's relative minor [e.g. the piece ends with and/or starts with the relative minor's root note]).

The third method is useful when sitting at the piano and being asked to play a minor key's scale; you can start playing it as the Major key's scale, and then flatten the 3rd note (and the 6th note if your asked to play the Natural minor, and the 7th note if you're asked to play the Harmonic or Natural minor).

Solving a Piano Student's Nightmare

You just sat down at your instructor's piano, and she says: "So, you think you know your scales, huh? Give me two octaves in contrary motion for the relative melodic minor of A Major."

What to do? First, we need to find the relative minor of A Major. That would be three clockwise steps around the circle of fifths from the A: (using the mnemonic described in a bit, this would be: "...(0)And (1)Endlessly (2)Battles (3)Father"): F#.

Now that we have the F# we know which root note to start on (F#). You can proudly announce "The key of F Sharp melodic minor" to your instructor, then start playing the A Major scale starting at F#. Since it's the melodic minor, remember to raise the 6th and 7th notes you play by 1/2 step (i.e. raise the D to D# and the E to E# [i.e. F]).

Alternatively, you could just play the F# Major scale, remembering to lower its 3rd note 1/2 step.

Either method will result in the same keys being played on the piano for the F# melodic minor scale:

Note # | A Major with F# as root & raised 6 & 7 | F# Major with 3rd note lowered |

| 1 | F# | F# |

| 2 | G# | G# |

| 3 | A | A |

| 4 | B | B |

| 5 | C# | C# |

| 6 | D# | D# |

| 7 | E# | E# |

| 8 | F# | F# |

Armed with just the facts above, you can now build any scale: major or minor, starting with any note! Just follow the interval pattern for either the major or minor scale.

For example, let's say you want to build a scale starting with the note F.

For a Major scale you would start with F, then go up a whole step to G, another whole step to A, then a half step to Bb, then whole steps: C,D,E, and finally a half step to F.

For a minor (natural) scale you would start with F, then follow the minor pattern: whole step=G, half step=Ab, whole step=Bb, whole step=C, half step=Db, whole step=Eb, then back to F. For harmonic minor, use the minor formula, but raise the 7th note 1/2 step (playing D instead of Db). For melodic minor raise both the 6th and 7th notes 1/2 step (playing D instead of Db and E instead of Eb).

Once you have a scale, you can build chords from it. Since each scale has 7 notes, there are 7 basic chords per scale: each starting with one of the 7 notes in the scale. A triad chord consists of three notes, and is named after the first note (root note) in the chord. There are several ways to construct these chords (i.e. different ways to choose the 2nd and 3rd notes of the chord). Some of these ways we also call Major and minor, but that does not mean that you can only have major chords in a major scale and minor chords in a minor scale. These designations (once again) simply refer to the pattern of the intervals between the notes. These patterns themselves are also known as Major and minor, and are as follows (with the number of half-steps shown in parenthesis):

| Chord Note | Major Chord | minor Chord | Diminished Chord | Augmented Chord |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (Root) | (Root) | (Root) | (Root) |

| 2 | Major (4) | minor (3) | minor (3) | Major (4) |

| 3 | minor (3) | Major (4) | minor (3) | Major (4) |

Another (possibly simpler) way to look at this is to always take the root note (one of the 7 notes of the scale) and then skip ahead two scale-notes for the 2nd note of the chord, and then skip ahead 2 more scale-notes for the 3rd note of the chord. This will give you the 7 basic chords of the scale, and they will fall naturally into the pattern:

| Root Note # | Major Scale | minor Scale |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Major | minor |

| 2 | minor | Diminished |

| 3 | minor | Augmented |

| 4 | Major | minor |

| 5 | Major | Major |

| 6 | minor | Major |

| 7 | Diminished | Diminished |

| 8 | Major | minor |

When writing a chord, it is customary to suffix the chord with "m" for minor, "dim" for diminished, and "aug" for augmented. It is also customary to write major scales and chords in upper-case, and minor in lower-case.

By far the most popular chords are the ones that start with the first, fourth, and fifth scale-notes. In the key of C Major, these would be the C (1st scale note), F (fourth scale-note) and G (fifth scale-note) chords. These chords are made of the following notes:

| Chord # | Chord Name (root note) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| I | C Major | C,E,G |

| IV | F Major | F,A,C |

| V | G Major | G,B,D |

Notice that every single one of the 7 notes of the scale are contained within those 3 chords. This means that by just using these three chords (the I, IV, and V chords in any scale) we can harmonize any note of the scale.

"Voicing" a chord means playing it in such a way that the top note of the chord matches the top melody note. This is accomplished by "inverting" the chord when necessary. A chord is said to be in its "root" position when the chord's name-note is the lowest note. For instance: C,E,G is the C Major chord in root position. We change this to its first inversion by taking the bottom note and putting it on top: E,G,C is the C Major chord in its first inversion. We create the 2nd inversion by doing this process again: G,C,E is the 2nd inversion of the chord. By selecting the root, or one of the inversions, the three basic chords can harmonize any scale-note. (When you play a chord in a sequence other than what could be arrived at via these inversions, it is said to be an "open" chord. For instance: C,G,E [putting the third note on top.])

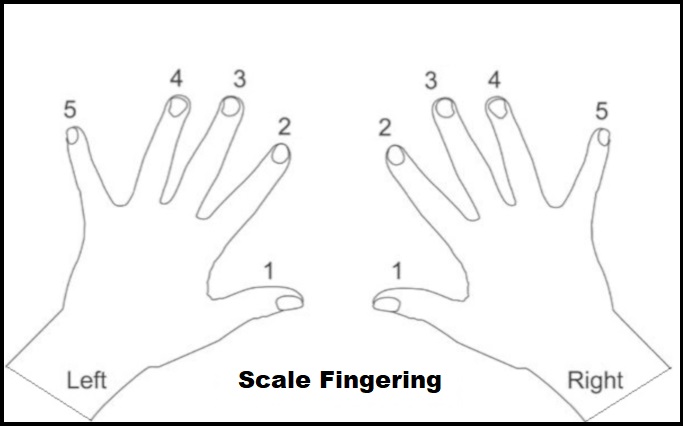

When playing a scale on the piano, it is important to use the correct fingers to play each note. On this page, the recommended fingerings are shown on the piano keyboard (with black numbers for the bass [left hand], and red numbers for the treble [right hand].) 1=thumb, 2=forefinger... 5=pinky.

Just as the 1st, 4th and 5th scale-notes are important in forming the most used-chords, they also indicate the relationship in chord (or key-changing) progressions. Look at the Circle of Fifths: it is called by this name because going clockwise around the circle each note is the 5th scale-note of the preceding key. For instance, we see C at the top, and G as the next key shown in clockwise order. This is because G is the 5th note of the C scale. Likewise, D (which is the next key shown) is the 5th note of the G scale. Going in counter-clockwise, the next key is the fourth-scale note of the preceding key. So, just by looking at the Circle of Fifths you can instantly tell that the 3 most-used chords in the key of C are going to be: C, G (the next key going clockwise), and F (the next key going counter-clockwise)!

Here is a mnemonic to help remeber the order of the circle of fifths:

The circle also helps in determining chord progressions. Here are some common progressions:

Sharps When there are sharps in the key signature, look at the last (right-most) sharp: what note is it? Add one note to it and that's the key. The sharps are always shown in the same order in the key signature: F,C,G,D,A,E. For example, when there are three sharps in the signature, you will see: F,C,G. G is the last sharp, so the key is A (since A is the next note after G). None of these key names have the word "sharp" in them except for F# (the one with the max number of sharps: 6).

Flats When there are flats in the key signature, look at the second-to-last flat: what note is it? That is the key. The flats are always shown in the same order in the key signature: B,E,A,D,G,C. For example, when there are three flats in the signature, you will see: B,E,A. E is the second-to-last flat, so the key is E flat. (These keys always have the word flat in them.) The exception to all of this is when there is only one flat: that is the key of F -- you just have to memorize that one.

First, figure out what the key would be if it was a Major key (remember they share the same key signature). Then look to see what note the song begins and ends on. If it's not the Major key's root note, but rather the Major key's 6th note, then it's likely to be the related minor key.

Back to top